Speed & Smarts: Light and Heavy Air Differences – Part 1

Jun 29, 2022

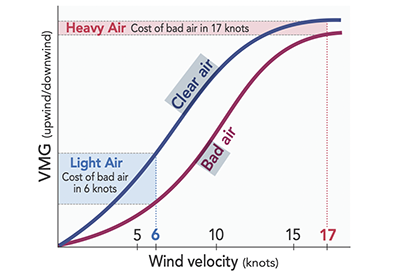

A boat sailing in bad air will obviously not perform as well as a boat in clear air, either upwind or downwind. But the relative drop in performance is not linear over the range of wind velocities. In light air, sailing in a wind shadow is much more costly than it is in heavy air (where there may be very little cost at all).

It’s clear that the more wind you have the faster you’ll go. That’s why sailors avoid the bad air of other boats.

The problem with sailing in wind shadows is that you have less wind velocity than boats sailing in clear air. This hurts in two ways. First, your boat speed is slower through the water. And second, you’ll have to sail lower (upwind) or higher (downwind) to maintain speed. Both are bad for VMG (velocity-made-good).

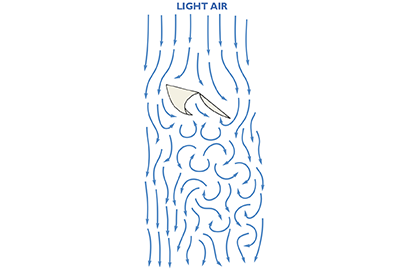

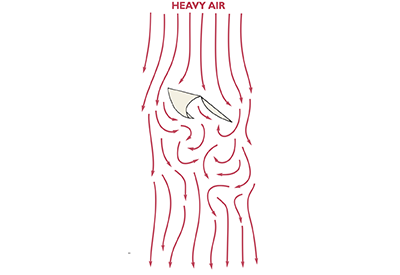

These problems are significantly worse when there’s not much wind. In light air, wind shadows are a bigger problem for two main reasons (see below): 1) they extend farther to leeward, behind and on the windward hip of other boats, so they affect a wider area; and 2) there is more turbulence within each wind shadow, so it hurts speed and height more.

In light air a small amount of wind makes a huge difference in your performance. So, losing even a knot or two of pressure (by being in a wind shadow) is much more of a problem than in heavy air. Being in bad air is similar to sailing in a lull on a puffy day: It’s a lot slower and you wouldn’t choose to do it.

Why wind shadows are larger in light air

These diagrams show a very approximate picture of air flow in wind shadows in light versus heavy air.

When the wind blows against a solid object like a boat’s sailplan, it bends around that object, breaks into eddies, and eventually returns to the way it was flowing before it was disturbed.

This turbulent flow (also called ‘bad air’) on the leeward side of every sailboat is called its ‘wind shadow.’ Since bad air is not good for performance, the key thing to know is how far that turbulent flow extends to leeward of a boat.

The answer depends a lot on wind velocity. In simple terms, the slower the air is travelling when it meets an object, the longer it will take to return to normal flow. In light air (left), therefore, a boat’s wind shadow is relatively large (maybe 10 boatlengths long). But in heavy air (right), the wind has enough energy to re-establish flow relatively quickly (after maybe five lengths). That’s one reason why you can feel the effects of bad air much farther away on light-air days.

It’s usually not a good idea to sail in bad air for very long, especially in light air. When there’s not much wind, you need every bit of pressure possible, so it’s critical to minimize time spent sailing in wind shadows.

When it’s windy, however, you are not as desperate to find extra pressure, and there is still quite a bit of wind in the shadows of other boats. So, sailing in bad air is much more of a strategic option.

If the wind was light, though, the cost of staying in bad air would be too high for pursuing all but the most significant strategic options.

Dave Dellenbaugh is the publisher, editor and author of Speed & Smarts, the racing newsletter. He was the tactician and starting helmsman on America3 during her successful defense of the America’s Cup in 1992 and sailed in three other America’s Cup campaigns from 1986 to 2007. David is also two-time winner of the Canada’s Cup, a Lightning world champion, two-time Congressional Cup winner, seven-time Thistle national champion, three-time Prince of Wales U.S. match racing champion and past winner of the U.S. Team Racing Championship for the Hinman Trophy. He is currently a member of the US Sailing Racing Rules Committee (and was its chairman from 2005-2008).

Dave Dellenbaugh is the publisher, editor and author of Speed & Smarts, the racing newsletter. He was the tactician and starting helmsman on America3 during her successful defense of the America’s Cup in 1992 and sailed in three other America’s Cup campaigns from 1986 to 2007. David is also two-time winner of the Canada’s Cup, a Lightning world champion, two-time Congressional Cup winner, seven-time Thistle national champion, three-time Prince of Wales U.S. match racing champion and past winner of the U.S. Team Racing Championship for the Hinman Trophy. He is currently a member of the US Sailing Racing Rules Committee (and was its chairman from 2005-2008).

You can subscribe to the Speed & Smarts newsletter HERE.